What the Comments Really Say About Türkiye

An analysis of 1,800 responses to Türkiye’s political unrest across the Financial Times, New York Times, and The Economist…

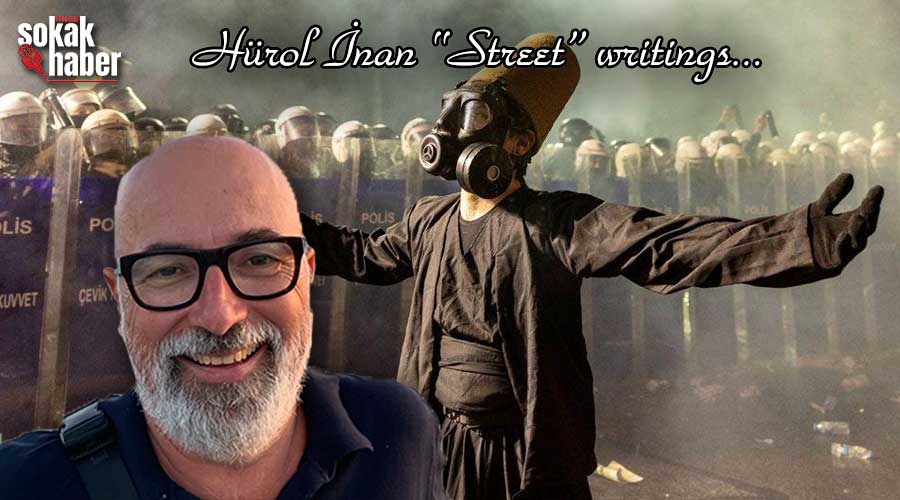

Hürol İnan – 29 Mart 2025

Over the past week, thousands of people from around the world have commented on news coverage of the mass protests and arrest of Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, one of the most prominent rivals of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The protests were met with harsh police tactics—tear gas, rubber bullets, mass detentions—and yet, international media coverage remains remarkably subdued.

Curious about the global public response, I turned to the comment sections of three widely respected publications: the Financial Times, the New York Times, and The Economist’s Instagram post on the same topic. I read more than 1,800 comments in total and analysed them with the help of ChatGPT, categorising them into three broad groups:

Group 1: Supporters of the Protests and Turkish Democracy

(Estimated share: ~60%)

This group includes many Turkish citizens and international observers expressing outrage at the arrest of İmamoğlu and the treatment of protestors. They repeat and reinforce the narrative that Türkiye has already become an autocracy or is sliding fast into one. Their comments are emotional, urgent, and often carry historic resonance—drawing on Atatürk’s legacy, comparing Erdoğan to other strongmen like Putin, Trump, and Orban, and lamenting the global decline of democracy.

Examples:

“Democracy cannot be silenced. We stand with justice, truth, and the will of the people.”

“This is how power is taken. Slowly. Piece by piece. Trump is watching.”

“We are the soldiers of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk! ”

These voices are not just reactive; they are building a collective memory, archiving what is happening in real-time.

Group 2: Defenders of Erdoğan and the Current Regime

(Estimated share: ~25%)

These commenters defend Erdoğan passionately—often with slogans, nationalist affirmations, or claims that İmamoğlu is guilty of corruption. They frequently assert that Türkiye is a country of laws, and that Western media is manipulating the truth.

Examples:

“Recep Tayyip Erdoğan”

“Ekrem İmamoğlu was arrested for stealing billions, not because he is a rival.”

“Turkey is a democracy. Leave our internal affairs alone.”

This group sees criticism from Western media as foreign interference or neo-colonial condescension. Some comments are more organised and repetitive, suggesting possible coordinated messaging.

Group 3: Dismissive or Hostile Comments about Türkiye

(Estimated share: ~15%)

This is perhaps the most troubling category. These comments reduce Türkiye’s complex political situation to cultural essentialism, dismissing the country as inherently undemocratic or unstable. Some conflate political critique with disdain for Turkish people, while others deflect the issue entirely by invoking global double standards. Many reveal thinly veiled racism, Islamophobia, or an outdated civilisational lens that denies Türkiye’s pluralistic and complex but European aspiring identity.

Examples:

“What did you expect from a Muslim country?”

“Turkey is becoming like Iran. Let them.”

“They’ll never be part of Europe.”

Such comments flatten Türkiye’s identity, ignoring its secular democratic traditions, its dynamic civil society, and its long-standing place in Europe and Asia-Minor. They reveal not just prejudice but a failure of imagination—a refusal to see Türkiye as a diverse, evolving society rather than a geopolitical stereotype.

It brings to mind Theodore Roosevelt’s observation: “To educate a person in the mind but not in morals is to educate a menace to society.” These commenters are not uninformed—they are engaging in elite media spaces like FT, NYT, and The Economist. But what’s striking is the absence of empathy and the ease with which moral judgment is replaced by cultural dismissal.

The Missing Group: The Silent Majority

Most surprising was what I didn’t find: large numbers of readers from democratic countries expressing solidarity or concern. This “missing fourth group”—the morally attentive citizens of other nations who would normally speak up—has gone quiet.

Why? Is it fatigue? A sense of helplessness? A belief that Türkiye’s struggle is “not our issue”? The silence from ordinary citizens, not just governments, is revealing. It’s not neutrality. It’s abdication.

What Do These Voices Mean?

Together, these comments form a kind of digital agora. They reflect not only the polarisation within Türkiye but how the rest of the world perceives its political struggles. The mass protests are clearly about more than one mayor’s arrest—they are a referendum on Türkiye’s political future.

But they are also a mirror. They show how divided we’ve become in responding to democratic backsliding—how eager we are to take sides, how slow we are to show empathy, and how rare it has become to speak out on principle.

Sources Reviewed

Financial Times

Europe can’t repeat its mistakes in Turkey – 133 comments

Turkish protesters rise up against Recep Tayyip Erdoğan – 247 comments

Turkey formally arrests Erdoğan rival – 111 comments

New York Times

What We Know About the Turmoil in Turkey – 55 comments

Turkey Arrests Istanbul Mayor, Erdogan’s Top Political Rival – 19 comments

The Economist

Has Turkey Become an Autocracy? (Instagram) – 1304 comments

Total comments analysed: 1,869

Analysis conducted using ChatGPT to assist with thematic categorisation, tone detection, and synthesis of common narratives across platforms.

A Personal Note

I was born and educated in Türkiye, but for the past 35 years, I have lived mostly in Australia and now split my time between Australia and Spain. Though geography has shifted, my connection to Türkiye remains deeply rooted. I care deeply—not only for the country of my birth but for every human being and every part of this universe we share.

Nationality is not a boundary to my empathy. I reflected on this more fully in a piece I wrote to mark Türkiye’s centenary, which you can read here. The point remains: what happens in Türkiye is not just a Turkish issue. It’s a human issue. And if we still believe in a shared moral conscience, then silence is never neutral.